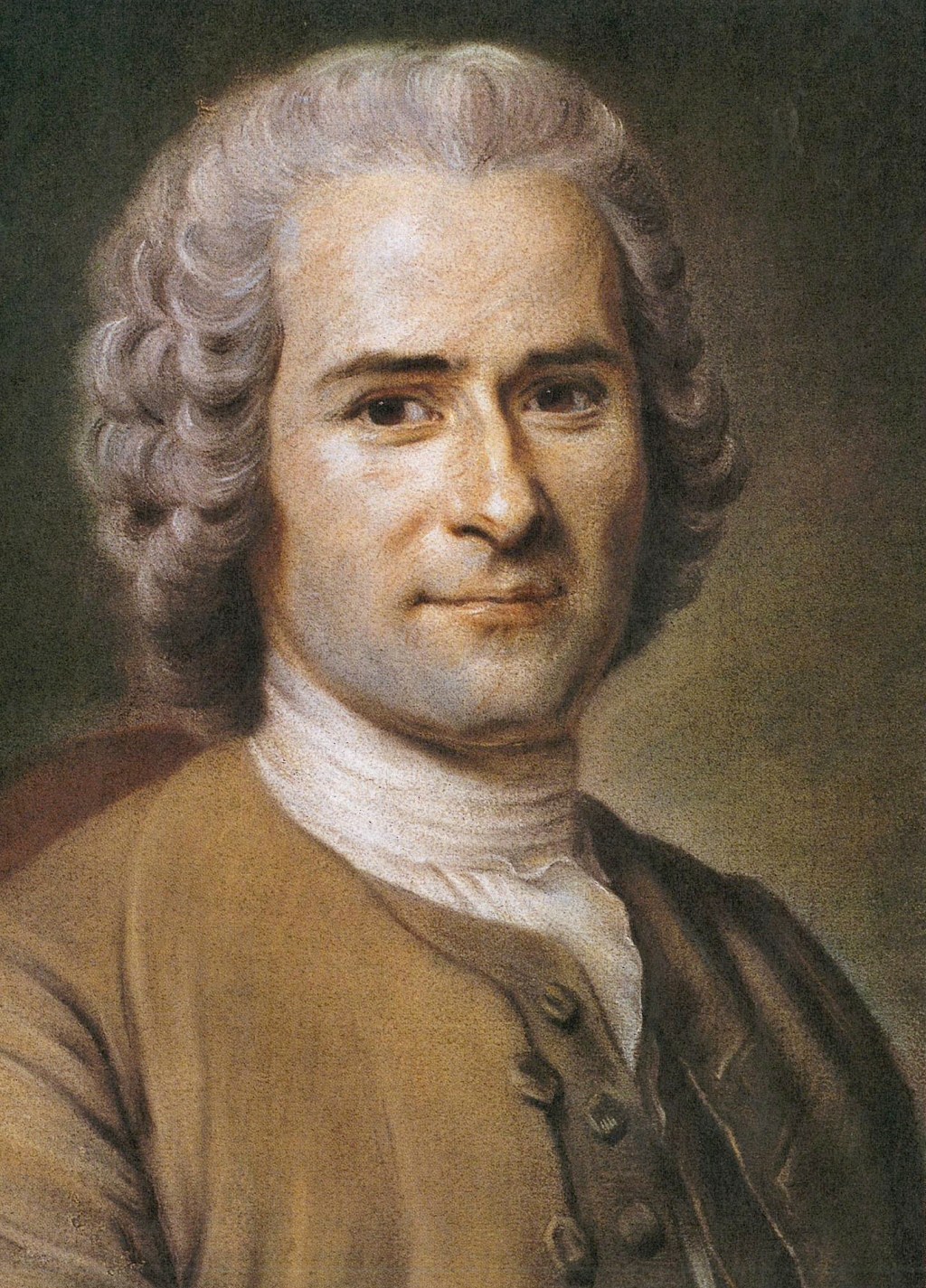

Book 1:

In his Social Contract, Rousseau does not actually want to answer the question how man, born free, came into chains but what can make such a state legitimate. Rousseau makes several setups, that help support his later argument. Firstly, he refutes Aristotels argument that man is a political animal (by nature). The reason he does this is because if man was not by nature political, there would be no need for a social contract, because people would be born into their political state. Secondly, Rousseau refutes „the right of the strongest“. He says that the word „right“ adds nothing to force. If one is the strongest, there is no need for him to have a right over oders to obey. Thirdly, Rousseau talks about slavery and inequality. In his mind, slavery by nature cannot exist, because it is much like a contract, where both parties have to gain something in return. This cannot be the case with slavery- slaves do not gain anything from it. Having laid these fundamentals, Rousseau comes to speak about the Social Contract.

- „The problem is to find a form of association which will defend and protect with the whole common force the person and goods of each associate, and in which each, while uniting himself with all, may still obey himself alone, and remain as free as before.” (p. 14.)

Man in the social contract is therefore bound in a double capacity: He is on one hand a member of the sovereign (leader), and on the other hand a member of the individuals under the sovereign (subject). The sovereign itself becomes an individual with a general will.

Book 2:

Rousseau goes from two premises of the sovereign: (1) Sovereignity cannot be inalienable; it cannot defer its power to a smaller group, because it always has to express the general will and (2) that sovereignity is indivisible; it always expresses the general will as a whole, not as some part. Furthermore, the general will is always right, as long as it is not, in a sense, corrupted by partials who themselves express the general will and with that the particular will to the state. Each member should think for his own – Rousseau seems to be an advocate of todays direct democracy. But what should the sovereign do with people who act against the general will?

Rousseau says that the sovereign has a right to bring the death penalty upon such people. But the sovereign is not the one to decide for who is subject to the death penalty; for this is the job of the law- but what constitutes the the law and who creates it? Law is when people decide „living-rules“ for all people. It is what maintains the body-politic, the social contract. Laws represent a leap from human nature into civil society and allow people „real freedom“, i.e. the ability to deliberate rationally. If our ability is not regulated by law, we are slaves to our instincts. A lawgiver (legislator) is somewhat of a saint or a prophet. In any case, Rousseau associates the creaton of laws with the supernatural. Rousseau himself even wrote to constituions: One for Poland and one for Corsica; though both were overtaken before getting into use.

It becomes clear at this point, that Rousseau has different meanings of the term „freedom“. In particular, he differentiates three types of freedom: 1) Natural Liberty, i.e. the freedom in the natural state, acting independently without any rules and solely upon instincts. 2) Civil liberty, i.e. the right to property by law, meaning the liberty to own certain things, without anyone taking it away from you (and not fearing this). 3) Moral liberty, i.e. when people have „self-mastered“ themselves. They can ask if they really want something (vgl. First order and second order desires). Someone who is addicted to something is not morally free. This freedom requires the general will and results in rational and thus actual free human beings.

The people, that constitute the sovereign have to have certain requirements, before being fit for a social contract. Firstly, the people that the legislator gives his laws to have to be fit for them (architect-ground analogy). When people grow old, it is hard to make them change their minds, because they have already adapted to their commons. Secondly, the state cannot be to big, because administration gets difficult the larger the distance gets. A state should be careful about expansion. Thirdly, there is a certain relation required between territory and amount of people: The right relation is that the land should suffice for the maintanance of the inhabitants, and that there should be as many inhabitants as the land can maintain.

Isaiah Berlins critique on Rousseau:

Steven Affeldt on „Forcing to be free“:

In his essay on Rousseau about „Forcing to be free“ discusses what is actually meant by forcing someone, i.e. in what way people would have to be forced. He firstly discusses what he calls the natural seeming interpretation. This line of interpretation says that the individual owes to the state – by way of entering the social contract – obedience to the law and bringing his particular will in accordance to the general will. Furthermore, an individual must only constrain someone if one does not obey the law.

Affeldt however refuses this interpretation and says that what the individual actually owes the state is continious participation in the effort to constitute the general will. This, according to Rousseau, is also what makes the law: The law is always the result of the current general will. Hence, if someone obeys the law, he is already lost; for he is not participating in the general will and therefore is not a citizen at all anymore. Why would someone then have to be forced to be free; what is the thread to society?

The threat to society, Affeldt says by quoting Rousseau, is the private will. The private will is what man desires by nature as a stupid, uncivilized animal. The private will is a threat to society because it is a continious temptation of man towards human nature. The question can now be asked as to what is there to do if someone uses his private will instead of the general will, i.e. how can he be forced to be free; forced, to use the general will?

At this point of the essay, Affeldt comes to speak of the similarities of Rousseaus social contract and Platos cave allegory. In Platos cave allegory, people who have been enchained in a cave, believe themselves to be in the true world but in fact that is an illusion. It is the task of the philosophers to free them from the chains and lead them towards the light. Similarly, Affeldt believes that Rousseau – by himself practicing it – sees the solution of „forcing people to be free“ in educating them about the state that they are in: philosophy, if done right, makes people aware of the chains that they have, and attracts them to the idea of true freedom, which lies in the continious participation of constituting the general will. Freedom must be recognized as a state within us; and it is through the force of this recognition that we are attracted to constrain ourselves – to the general will – and seek the realization of true freedom.